.

If you haven’t read the Vulture exposé on Neil Gaiman, here it is. It ain’t pretty.

I first heard about this in hints from William Morris; I did not immediately seek out more information. Perhaps for the same reason I take issue with this observation:

Don’t people deserve time to grapple with new information? to mourn?

William’s responding to a fellow who said that the only appropriate response to Gaiman’s actions would be life in prison. Which I find even more troubling.

I want to be clear: in no way am I defending Neil Gaiman. But we as Americans are already way too happy sending our fellow citizens to prison. This call for suffering to solve the problem of suffering is never great but in a time where we are battling authoritarianism within our own nation, that impulse could be used against us in a hurry.

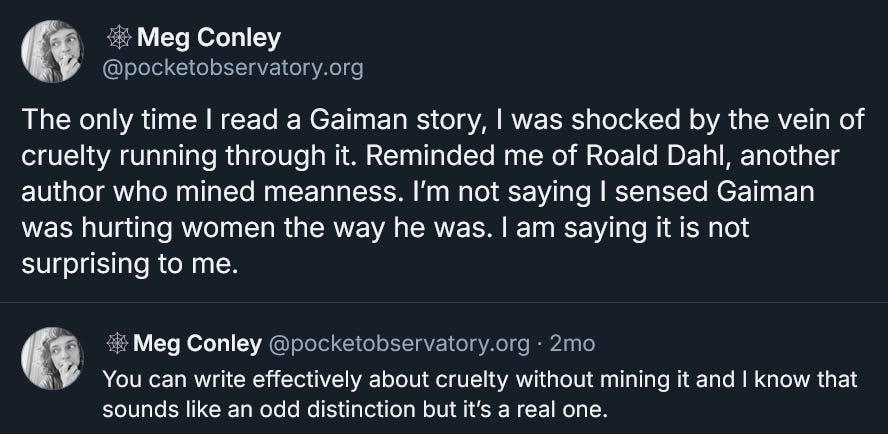

But I never would have written this little essay were it not for something another friend posted on Bluesky:

This led to others (including people I like quite a lot) piling on, saying they’d always felt this about him and complimenting the term “cruelty mining” as being just the right critical lens through which to view his work. To the exclusion of all others, I suppose.

Again, I’m not here to defend Gaiman’s actions as described in Vulture. They’re abhorrent and sad. But we’ll get to them.

My first thing, the thing I felt I had to say something about, was this Calvinistic take of Meg’s and how I find it deeply troubling.

The fact that folks from many marginalized groups have found themselves in Gaiman’s work for decades should count for something. His longtime allyship with Tori Amos, including in her role as public rape victim, should count for something. That women in particular have felt seen and accepted through his work should count for something. Discovering his late sins does not retroactively turn him into a monster-since-birth.

Reminds me of a seven-year-old who knew the penny was heads all along—as soon as he sees it is heads (whether he had said heads previously or not).

Anyway.

Enough with knocking the rhetoric of my friends.

I’m on record (many, many times) as saying that Gaiman’s shorter work is better. His comics, short stories, and children’s novels tend toward the excellent. I haven’t read a single novel of his for adults that struck me as all that good.

(A list of reviews [likely incomplete] available over on Thutopia: The Sandman [comics]; “Metamorpho” [comics]; Fragile Things [short stories]; Best American Comics 2010 [as editor]; Chivalry [comics]; Fortunately, the Milk [children’s novel]; Norse Mythology [retellings;] Trigger Warning [short stories]; Black Orchid [comics]; The Graveyard Book [children’s novel]; Neverwhere [novel]. Among the other works I’ve read but are not listed here, probably because I read them before I started keeping track, are Coraline, Smoke and Mirrors, American Gods, Death: The High Cost of Living. Also, little books like picture books generally don’t get reviewed. Yet no matter how you count, I’ve read a good amount of his work.)

I’m struck now by a story that appeared in Smoke and Mirrors, “Tastings.” This is a super-graphic story that takes place entirely during a sex scene. The costly male prostitute is wonderfully successful at his job because his has psychic powers that let him know what women want, nibble by thrust, before they know it themselves. This preternatural skill, as you might imagine, makes him very popular. In the story, however, the woman he’s having sex with is some sort of succubus who sucks away all his psychic powers. And while he will remain skilled at the sex, something is gone that will never return.

It’s easy to see myriad ways this story might apply to the Vulture story, but I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

What I’m thinking about more than the story itself is the author’s note for that story. And just how embarrassed Gaiman was to have written it. He was as shocked as we were. Even through the words on the page you could see the red in his cheeks. He had fulfilled the assignment he was given but he wasn’t sure how to feel about it.

The first time I was disappointed in Gaiman as a person was 2007 when he divorced his wife of 22 years. This felt like a true celebrity divorce; behold! a man who had found fame and success and fans upon fans upon fans—then suddenly discovered he was too cool for the wife of his youth, for the mother of his children. That decision felt then (and now) portentous. While his art might survive the transition, it seemed probable that his soul was now a different man’s soul.

This, too, is judgmental, I admit. But I want to be clear that my judgment, while also faulty and preferably avoidable, is based on actions and not my “always was” reading of a person’s art. The reason I was saddened-but-not-surprised to hear of this once-good man’s fall is because he had already fallen—when he left his family. Not because I didn’t like American Gods.

The Vulture article reveals a man who has now had decades of experience justifying one thing and then another thing and then another thing until he became a monster.

Now, sure, we might find out next that he was a-raping people in 1992, and that will be a new conversation. But let’s not assume that.

What’s troubling me now, what I need to speak out against today, is how, upon uncovering a crime, voices insist this person was predetermined for hell. I don’t believe that. I won’t believe that. And painting an entire person’s life (and work) with a brush dipped in their current sins is, I think, wrong. We shouldn’t do it.

It is better to mourn than to have been right all along.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment