.

Substack tells me that my AI/tithing post is Thubstack’s most popular. As twice the other week I was approached by friends about it, I guess that must be true. People do not often approach me about the stuff I throw on the internet.

Anyway, the second fellow wanted to tell me that his corporate overloads are demanding that he and his colleagues figure out how to integrate AI into their jobs. But! so far! it’s only slowing them down and making their jobs harder. (This seems to be true for everyone in all fields—even for coders, the people AI can supposedly best assist.) By the way, this fellow doesn’t work for an AI company. So the bossmen have been paying money with the wild belief that, contrary to all evidence, AI will make them more money than they’re spending on it. Not likely, but the good news is: all that money may help one lucky AI company keep their lights on a little bit longer. I’m a big fan of charitable giving.

As for the first fellow who approached me, his career is deeply entwined with AI. It’s not an exaggeration to say that AI as currently constituted may not have happened without his genius. And he is a genius. Make no mistake. But, outside Victor Frankenstein (really, only outside the book version of Victor Frankenstein), creators are compelled defend the worthiness of their creations. And that’s what he wanted to do in response to my post.

Interestingly, in his email, he rhetorically equated AI with Mormonism. That is:

me : mormonism : : him : ai

Which feels telling in retrospect, even though his questions were all about where the artificial fits within a Mormon worldview—after all, is not all truth part of one great whole?—the assumption being, I think, that if it is all one great whole, then “artificial” becomes an artificial category. If God can work through human hands, why not through human tools? These are reasonable questions and made me feel I should get a bit more precise as to what I think the problems with AI are.

In my previous article, I argued that anything worth doing is worth doing oneself. Tools may assist a person in doing a thing, sure, but people seem attracted to AIs because they imagine they will allow them to avoid doing the thing. Which, I suppose, makes their argument simply that those things are not worth doing. Honestly, this is how I feel about much assigned schoolwork and probably lots of corporate work as well. But maybe the better solution is just do not do those things? Don’t make kids write a paper that’s boring! Boom!

Anyway, I’ve since found something the Church is using AI for that I find reasonable. If you go to FamilySearch now, on many of the deceaseds’ pages, you’ll find something like this:

It’s adequate and simple enough that it’s unlikely to get anything important wrong. Plus, it’s easy to replace with something you yourself have written should you be so inclined. I don’t know how much they’re spending on this (or how much the contracted AI company is losing regardless), but maybe this is worth doing? It seems reasonable, anyway, so long as it doesn’t prevent people in North Carolina from drinking water. It’s not really offering anything you couldn’t discover with another click or two and twenty seconds of reading, but okay.

Another “reasonable” use I saw at church recently was related to our ward’s upcoming 100-year anniversary. As part of that, we’re writing a history and someone on the committee inputted forty-years of ward newsletters into ChatGPT and let it write a couple chapters. These things were terribly written: filled with cliches, poor editorial decisions, factual errors, the sorts of repetitive writing seventh graders use to reach a pagecount, etc. But it was a start. Since then, members of the ward have put in…I would guess well over two hundred hours rewriting it (including research, deletions, additions, corrections, smoothings, and so on). It was helpful to have that awful beginning to get us started, but it did not save us time in the long run. It’s a current debate whether as to it was actually worth doing at all. Personally, I suspect we wouldn’t have met our deadline if we weren’t rewriting a draft that appalled us. Which is a fun irony as using AI also took us more total hours. Ha ha ha. Procrastination strikes again!

My friend (the first fellow) also brought up one of his favorite metaphors that he’s been using for over a decade now:

“Is a beaver dam artificial?”

I suppose that depends on how you define “artificial” which I am (obviously) avoiding, but I love the comparison of an LLM to a beaver dam because that comparison highlights exactly what is problematic about LLMs.

Which finally brings us adjacent to the promise of my title. So let’s pause our beaver-talk while I suggest a few examples of what’s so bad, theologically, with AIs. The most terrifying things that I’m witnessing include:

• The whole point of life on Earth from a Mormon point of view is to learn by exercising agency. What I witness pretty much every single time I hear “ChatGPT” in a sentence is someone surrendering their agency. They’ve surrendered an opportunity to think a thought or to create something new, then been impressed by (see next bullet point).

• LLMs are, necessarily, dedicated to the averagization of human culture. They’re pattern machines that model themselves after extant patterns. While you can throw tweaks into their behaviors, they work by matching what’s come before. That’s why they can only be as good as the data that is (stolen and) fed to them. It’s why they need the entire internet to sound smarter than one of Janelle Shane’s bots. It takes a great deal of people (and some fancy programming) to make AI sound smart. But even then, only when you don’t look closely. Or when you yourself (see next bullet point).

• AI products are accelerating the enshittification of civilization. You can find reasonable/angry people on YouTube ranting about this, but we all know it’s true. Deepfakes don’t make civilization better. Grok’s political opinions don’t increase the health of democracy. Salt substitutes aren’t making people healthier.

Another friend of mine recently wrote this:

…my primary belief [is] that human identity and consciousness consists of attention and intention.

Attention and Intention are at the core of almost every metaphysical practice. Religious ritual, magical practice, meditation, journaling, whatever you might have as “that thing that moves you beyond the basic existence of production and consumption.”...

The interplay of attention and intention is to me why the doomscrolling-algorithm practice is demonic and destructive. Forget the neurological aspect of it, it’s an active practice in de-soulment. You are turning off all intention. Doomscrolling is nihilistic in that it gives up all will and forfeits it to the ba’algorithm.

There is no attention to be paid here—because attention implies agency and doomscrolling is not something we (and I’m including myself here purposefully) actively choose....

There is no intention to be made here—because intention implies a purpose or something that is gained either at the end or through the medium of the activity. The end of a doomscrolling session is never because you have reached some level of satisfaction but because some other thing beckons you.

This is as simple and coherent an explanation as could be made. LLMs are designed to accelerate the ba’algorithm’s work. While pattern machines are already proving helpful at letting oncologists get through more images (good) and pick nonwhite people out of a crowd (not good), there are also some reasonable arguments for human interaction, for instance, AI’s potential to help the lonely, it may also accelerate our disenfranchisement with ourselves as lovers, as parents, as members of the entire human project. (I mean—it definitely will if there’s money in it. Capitalism isn’t built to care about the future.)

And this brings us back to beavers.

While its true that the Luddites hated machines that took away their ability to do a craft (although it was more complicated than that), ultimately most human-invented tools have ultimately provided more opportunities for thinking and enrichment; LLMs, as currently used, persuade us not to do such things. Or, rather, it allows people to pretend they’re thinking and creating when in fact they are not. It allows people to lie to themselves.

But what do beaver dams do? Well, they do more than just give beavers a place to raise baby beavers.

Let’s pause here for a moment to point out that what beaver dams are doing are increasing the potential for agency—they’re creating an ecosystem that allows duck and mink and otter and smelt and steelhead and salmon to do their thing. To have offspring after their kind. To have joy. But sorry for interrupting.

• Beavers regulate water flow, preventing sudden floods.

• Beaver ponds store groundwater.

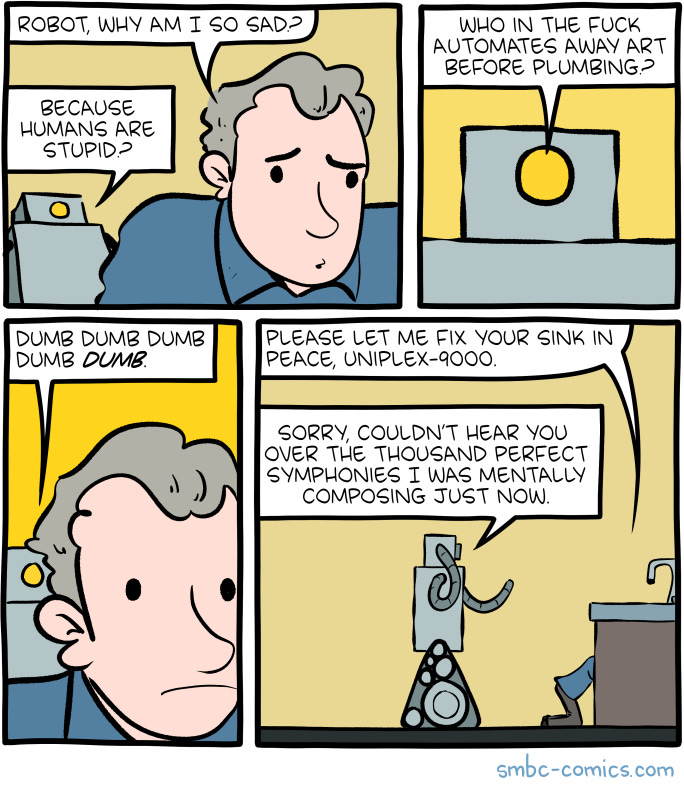

In other words, beavers’ dams do a great deal of work, they do a great deal of good. In short, they are what AI boosters claim AI is / will be rather than what AI has proven to be so far. It’s an old joke (and gives the robots too much credit), but SMBC probably told it best:

Look. Saying you have emails ChatGPT can write is admitting your job consists of emails that do not need to be written and do not need to be read. I’m not sure that’s how we should live our lives anyway. Perhaps—just perhaps—what these LLMs are revealing is that much of the world capitalism has built us is already contrary to a life well lived. Perhaps we are discovering that tasks we have called important are just glorified averaging. Perhaps we have spent hours and hours and hours engaged in tasks that never needed to be done.

Students who cheat, who use a machine rather than writing their own work? Perhaps that’s because their human instincts correctly recognized the assigned work wasn’t worth their time. (Or perhaps they’ve been fooled into believing it’s not worth doing which may be worse.) Teachers using AI to make assignments that are a waste of students’ time are committing a sin orders of magnitudes greater.

I go on accreditation teams to examine schools. The accreditation agency recognizes that much of what they have us do is a waste of time. How do I know this? Because they tell us to write our report by feeding the schools report into AI. Which implies they assume schools are using AI to make those reports and suggests they use AI to read our reports. If no human needs to be involved, it ain’t worth doing.

My teams so far have eschewed AI and we thus actually get to know the schools rather than simply appearing as if we do.

Of course, don’t take my word for it. Even OpenAI, which is constantly making absurdly optimistic predictions about AI, has said LLM hallucinations are a mathematical certainty. In other words, AI producing bad outcomes (lies?) is, according to OpenAI itself, a permanent state of affairs.

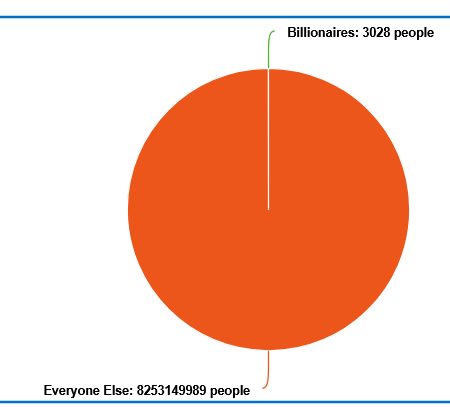

But it’s not just that LLMs are liars from the beginning. There’s also no question that some people absolutely and openly see LLMs as a means of controlling those who must be controlled. Which is all of us. Because billionaires are a rounding error.

(Had to give them a single pixel because otherwise they wouldn’t exist. Billionaires did not earn their pixel.)

It might seem I’ve gone far astray from my original promise to discuss the theological implications of AI. But I haven’t.

In a moment where Nvidia is trading chips for OpenAI stock, thus either bleeding OpenAI for whatever VC they have left or tying themselves to the ship about to sink in hopes that will prevent it from sinking—in a moment where our entire economy is “not in a recession” entirely thanks to spending on AI—in this moment, in other words, we need to reassert our humanity. Each of us needs to assert our humanity as individuals, and we need to assert belief in the actual true real imaginable humanity of everyone else as well.

Part of what AI salesmen try to tell us is that AI will increase human dignity. Instead of doing menial tasks, we’ll be free to accomplish great things. Each of us! Individually!

But instead, so far at least, they’ve offered soma. They’ve offered products that would remove our intention. They’ve offered products that would devour our attention. They‘ve offered products that would slowly remove our ability to create, our capacity to choose, our drive to be agents unto ourselves.

And as a Latter-day Saint?

Such is the purpose of life, baby. To create—to intentionally create and choose and become. To do what we can to allow others their dignity as they too create and choose and become. That’s why we’re here. That’s why God put us here. That’s what it’s all about.

That is my theology.

And even before we get to how this system is flooding more and more of our economy to fewer and fewer of our people, it’s why I can’t boost AI.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment